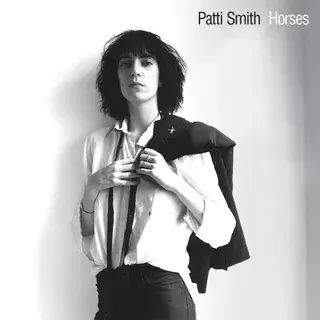

Belief, Defiance, and the Birth of a Gospel: Patti Smith’s "HORSES"

- Mason Morgan

- 8 janv.

- 3 min de lecture

Patti Smith is a poet, performer, and punk-rock prophet whose work collapses the distance between art and belief, turning language into something lived rather than merely heard. Emerging from New York’s poetry scene in the early 1970s, Smith fused spoken word, rock ’n’ roll, and spiritual defiance—most famously on her debut album Horses, where her voice, history, and conviction rewrote the rules of performance and transformed personal truth into cultural scripture.(Rock)

It’s a fine line Horses between listening and believing when it comes to Horses. Even before the decades turned Patti Smith’s debut album into rock’n’roll scripture, its eight-word opening salvo imbued its body and blood and grace and guts with a holy truth. “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine," was sung-spoken slowly, like smoke. Our story begins at church, on Bertolt Brecht’s birthday, Lou Runder a eed in the pews, full moon.

Patti stepped to the lectern at the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church on February 10, 1971, and dedicated her reading to crime. From the moment she opened her mouth, her brash South Jersey accent and out-of-step real talk demolished the fourth wall between performer and audience. The date marked Smith’s first gig with guitarist Lenny Kaye, a music critic she befriended after he wrote about the early-60s phenomenon of regional street-corner vocal groups (“The Best of Acapella,” Jazz and Pop, 1969), the doo-wop of her own youth.

She recruited Kaye for St. Mark’s by asking, “Could you play a car crash with an electric guitar?” Having produced Nuggets—the 1972 garage-rock compilation of willfully unprofessional 60s bands already dubbed "punk rock," Kaye was game. The East Village church was not typically host to electric guitars. Smith had attended past readings at the Project alongside Beat scribe Gregory Corso, who would heckle dull poets (“No blood! Get a transfusion!that ”) and she promised herself if she ever had a chance to read her own poetry, she would never be boring.

That night, she sang “Mack the Knife” and performed her poems, including "Oath," the origin of her "Jesus died..." line, before a crowd that included Andy Warhol, Bobby Neuwirth, Robert Mapplethorpe, Sam Shepherd, and Anne Waldman. Afterward, her soon-to-be friend Sandy Pearlman suggested she front a rock’n’roll band, “but I just laughed,” Smith wrote in her 2019 memoir, Year of the Monkey, “and told him I already had a good job working in a bookstore.” Immediately, she was flooded with requests. A businessman offered a lucrative record deal, hoping to make her into the Downtown Cher. Her response was, "I ain't never gonna do this. I ain’t never gonna do a record unless they let me do exactly what I want.”

She had fled rural South Jersey in 1967, leaving behind her family home, which was located across from a square-dance barn, and her non-union factory job to “get on that train [...] and go to New York City,” as she would chronicle on her first single, and “be somebody” and “never return, no, never return/To burn out in this piss factory/And I will travel light, oh/Watch me now.” New York was all eyes on her.

All these Patti Smith genesis myths have become as seismic as her music. The fable of her young bohemian existence—CBGB, Chelsea Hotel, Mapplethorpe, Cowboy Mouth—precedes her. It can be summarized by saying she believed in herself—a sickly child and the oldest of four to a waitress mother and factory-worker father who moved 11 times before her fifth birthday. As a young Jehovah's Witness, she would knock on doors on Saturday mornings, she eventually dismissed organized religion when an elder told her there was no room for art in God’s kingdom. She found solace in poems, fairytales, Dylan, Coltrane, and imagined a way out. “I grew up in a tougher part of Jersey than Bruce Springsteen,” she told Rolling Stone in 1976.

Teen girls like her weren’t meant to escape. When she became pregnant and gave up a child for adoption at 20, “It developed me as a person, made me start to value life,” she said, “that I’m not down in South Jersey on welfare with a 9-year-old. ‘Cause every other girl in South Jersey who got in trouble at that time is down there.” Smith’s freedom was tangible. She left home with nothing in pursuit of everything, sharpening herself against the rock of experience and exalting the innocence of dreams.

Mason Morgan

Commentaires